Just off the coast of French Guiana, sit Les Iles du Salut, 3 islands with a dark past. I visited Ile Royale to discover what prison life was like on these Devil’s Islands.

Despite the beauty and biodiversity of its nature, and the openness of its people, French Guiana, like much of this stretch of South American coastline, has a brutal past. From colonisation came rampant tropical diseases, slavery, and much suffering of the indigenous peoples. Some of the darkest days were during the time of the penal colonies, from the 1850s to the 1950s.

You don’t have to look far to see the scars of the past. There are art installations, museums, and, most noticeably, ruins of the prisons of the past. These prisons, known here as ‘bagnes’, were located throughout the region and their ruins serve as daily reminders of this brutal past.

French Guiana was not always the tropical holiday destination it is today. In fact, during its penal colony days, being sent ‘en Guyane’ was the ultimate form of punishment, reserved primarily for the worst of France’s criminals.

Ironically, one of the most notorious of French Guiana’s prison colonies was located on Les Iles du Salut, or Islands of Salvation, three small islands, now serving as nature reserves and day-trip holiday destinations for the French Guianese. During prison times, they were collectively called Iles du Diable, or Devil’s Islands, a name that remains with the smallest of the three.

Ile du Diable is the smallest of the 3 Iles du Salut

I went to visit the largest of these, Ile Royale, to understand what life was like for the prisoners. But the journey to the island itself was a mini-adventure.

I love being on the water (and in the water) so I was happy to learn our ferry ride, from the old port of Kourou to Ile Royale, would take about an hour. But this was no ordinary ferry. We were sailing in style on a modern catamaran. Calm seas and a bright sunny morning made for a beautiful trip.

Riding to Ile Royal in style on the catamaran ferry

Leaving the old port of Kourou, we sailed past the Hotel des Roches where we spent the first 2 nights of our stay in French Guiana

Arriving at Ile Royale, we were met by M. Serge Colin, a retired marine captain, whose knowledge of, and passion for, the history of these islands is beyond compare. We climbed aboard his all-terrain golf cart and headed to the top of the volcanic island.

We began our tour at the Auberge de l’Ile Royale, where visitors can stay overnight, or enjoy a meal at the restaurant. (Read my full review in Where to Eat & Sleep in French Guiana.)

What I noticed right away was the abundance of wildlife on the island: iguanas, sea turtles (feeding along the pier), a macaw (apparently a pet of the Auberge, with free reign of the island), peacocks, and, everywhere I turned, agouti.

The wildlife on Ile Royale includes iguanas and agouti

The wildlife here doesn’t seem to mind the dark reminders of the island’s past

The agouti is like a guinea pig crossed with a rabbit.

Agoutis are small rodents that look like a large guinea pig with rabbit legs. They hop (and, apparently, breed) like rabbits, but have neither tails nor long ears. You can spot Agouti all over French Guiana, but here on the islands, where there are no large predators, they are everywhere.

But the theme of our tour was much more sinister than the local wildlife. Bypassing the agoutis, we followed M. Colin to a large, open square, lined with well-maintained buildings. These residences were once for the prison officers and now house the two gendarmes stationed on the island. Their primary job is to evacuate the Les Iles du Salut whenever there is a space shuttle launch, as the islands are directly under the flight path; a process we would experience in just a few hours.

The officers quarters overlook the prison complex

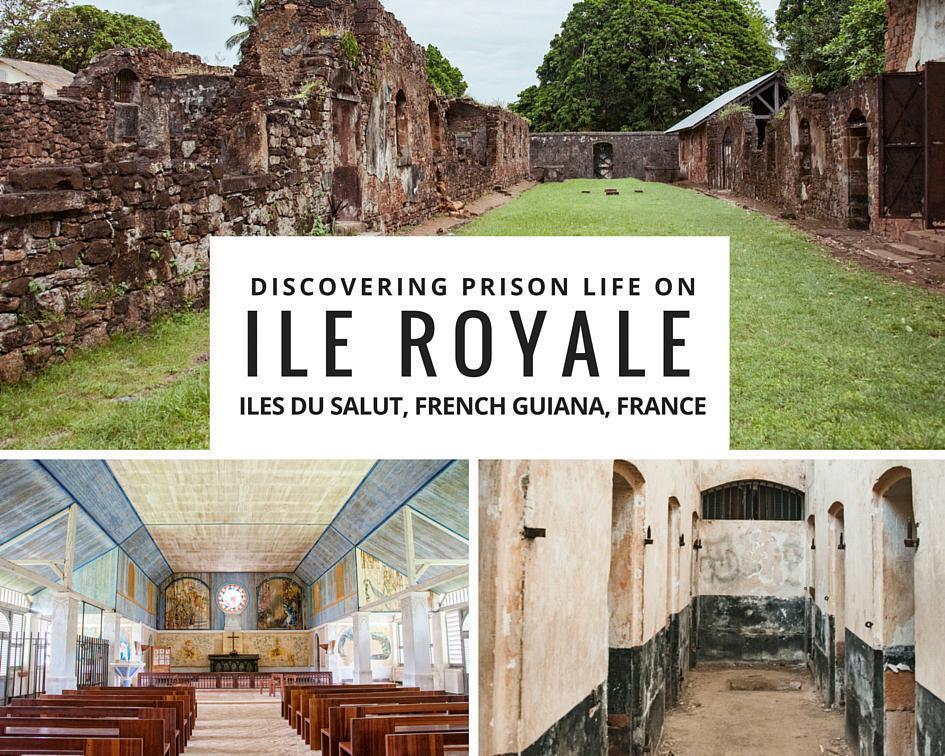

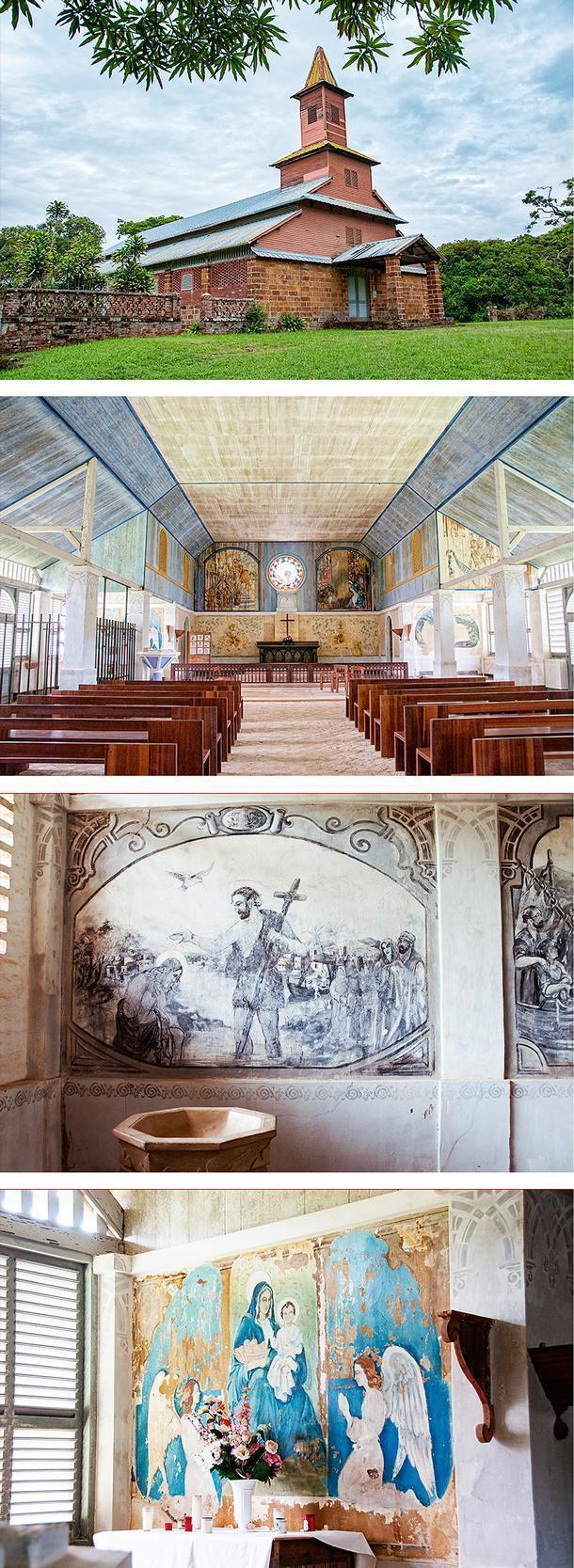

Beside the officers’ quarters sits one of the highlights of Ile Royale – the prisoner-built chapel, dating from 1855. The most striking features, inside the wooden church, are the murals painted by convicted forger, Francis Lagrange. Known as ‘Flag,’ Lagrange painted scenes of daily life in the prison, as well as postcard-like scenes of escapism and even erotica, for his fellow-prisoners. With the complicity of some of the prison guards, Lagrange even kept his forgery talents in practice, copying documents and official papers, earning him special privileges within the prison.

The chapel frescos are one of the highlights of the island

Tucked beside the church sits the House of the Sisters. Nuns arrived on the island at the same time as the prisoners. They tended the infirmary until 1904 when French law dictated the separation of church and state.

The largest building on the island is the military hospital. This building, however, was not for the prisoners, but rather military personnel stationed on the island. Wealthy citizens of Cayenne also stayed in the hospital for periods of convalescence away from the city.

The lighthouse guides boats past the Iles du Salut

The island’s lighthouse stands beside the hospital. Now automated, the lighthouse was once operated by a prisoner who was a mechanic.

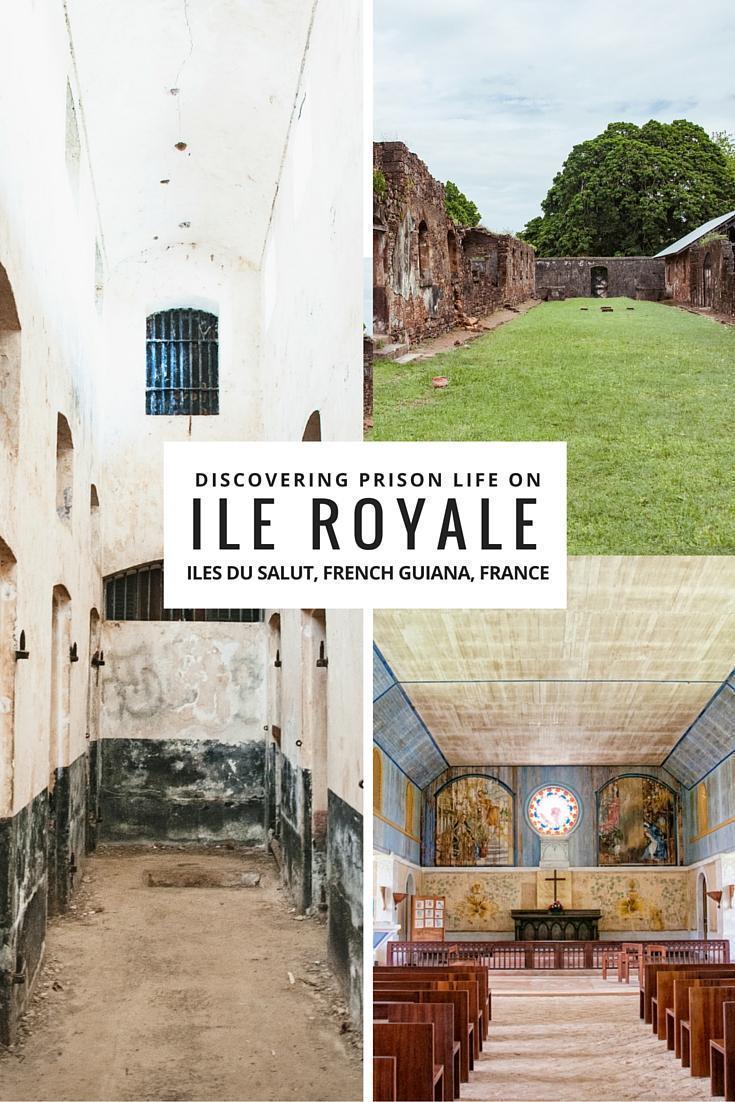

After our tour of the grounds, we entered the remains of the prison compound itself. Here, any mental image of a tropical island getaway disappeared.

The remains of the prison courtyard

In the early days, prisoners were shackled to a wooden plank, which served as their bed. In 1929, the planks were upgraded to hammocks; slightly more comfortable but still crowded together in impossibly small spaces.

Prisoners could also be sent to solitary confinement in one of 32 cells with small windows or 34 cells which remained totally dark. Prisoners in solitary were only fed soup and bread every 3 days. Some prisoners remained in these conditions for years. However, as many of them were convicted to death, it was marginally better than the alternative. Getting out of solitary meant facing the guillotine constructed in the middle of the prison courtyard.

Solitary confinement was even bleaker than the general population

It’s easy to see how most prisoners didn’t survive their sentences. Those few who did would rarely ever return to mainland France. In fact, for sentences under 8 years, a system called ‘le doublage,’ came into play. For every year of the sentence, an equivalent time must be served living in French Guiana, effectively doubling the sentence.

In all, between 1852 and 1938, over 50,000 prisoners died. A ‘lucky’ 1400 escaped, to face dense jungle and tropical diseases, and fewer than 300 lived to see eventual freedom in French Guiana. Despite a good deal of political pressure, it wasn’t until 1946, the prison was closed for good and the remaining 240 prisoners were released and pardoned.

In 1965, the Centre Spatial Guyanais opened in Kourou and in 1971 the CNES, Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales, purchased the islands. As they sit in the flight path of most rocket launches, the islands must be evacuated on launch days.

Sure enough, as the clock struck 1 pm, two rather large, armed gendarmes politely asked us to head for the ferry. I had no desire to test their politeness. I also had an appointment with a rocket I had no intention of missing.

Our ferry was much busier on our return trip, as it included all remaining visitors and staff on the island. Many visitors were loaded down with camping and picnic gear, as it is possible to overnight on Ile Royale.

Visitors are free to tour the island at their leisure and can learn more about prison life at the small Musée du Bagne, in the former Director’s home. However, to get the most out of your visit, it’s well worth taking a guided tour, which leaves daily at 10 am from the Auberge. M. Colin works only on weekends, so if you want to take advantage of his expertise, as we did, be sure to visit on Saturday or Sunday.

Stay tuned next week, as I watch 2 brand new satellites be launched into space from French Guiana.

Like this article? Save it to Pinterest!

Want to win your own trip to French Guiana? Vote for your favourite French Overseas experience for a chance to win a trip for two. (Open to residents of Belgium)

My travel to French Guiana was sponsored by Guyane Tourisme and Atout France Belgium. As always, all opinions remain my own.

- The Ultimate List of Castle Hotels in Belgium - June 10, 2019

- The Ultimate Guide to the Best Things to Do in Normandy, France - February 5, 2019

- The Ultimate Guide to the Best Restaurants in Brussels, Belgium - January 11, 2019

- A Voyage to Space, in French Guiana

- Discovering Prison Life on Ile Royale, Les Iles du Salut, French Guiana

- French Guiana’s Cacao Market by Boat with Wayki Village

- 3 Easy Ways to See Nature in French Guiana

- Exploring the Reserve Naturelle des Marais de Kaw-Roura, French Guiana

- Where to Sleep & Eat in French Guiana

- 5 Surprises in French Guiana

- CheeseWeb’s Travel Guide to French Guiana