[Editor’s note:] I am incredibly excited to have this guest contribution today, not only because it covers a part of Europe Andrew and I don’t know well, but because it’s by some folks who have had a big impact on our own travel story (without even knowing it.) When Andrew and I first decided we wanted to explore Europe by motorhome, several years ago, I discovered Jay and Julie’s blog, OurTour.co.uk. Not only were they traveling exactly how we wanted to, but they were sharing exactly how they were doing it.

I read every post on their site within a few weeks and it was a huge source of inspiration and motivation. Although we haven’t met in person (yet), we feel as if we know them, through their personal and honest writings about their travels. Jay has very kindly provided this insight into the Hidden Gems of Eastern Europe – in countries Andrew and I have been fortunate enough to visit, and some still waiting patiently on our Bucket List. Grab your beverage of choice and settle in for an inspiring read about our favourite style of Slow Travel.

“But we aren’t from Eastern Europe; Czech is in the centre of Europe…” I was sat in a bar in Nottingham, talking with a couple of work colleagues visiting from Prague. Having raised the subject of what it was like to live in Eastern Europe, they’d succinctly put me right; they didn’t even see themselves as coming from ‘the east’. That definition was temporarily imposed on them by the cold war’s Iron Curtain, and they simply didn’t see it as applying to them anymore, if it ever did.

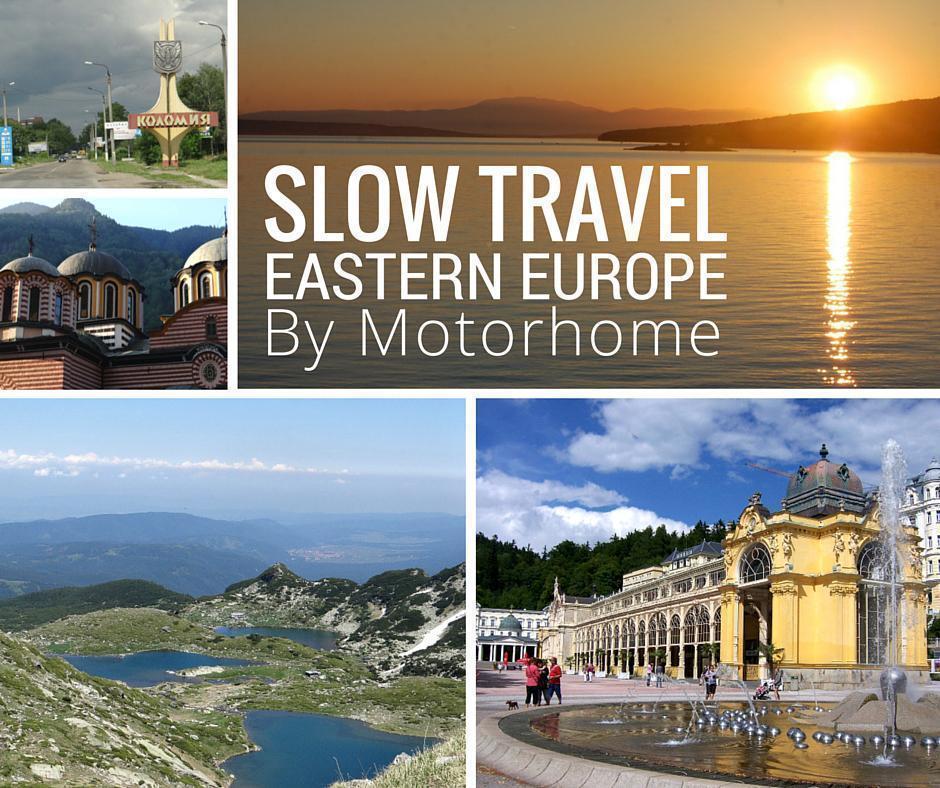

Marienbad, Czech Republic

Over time, Julie and I have been fortunate to travel a number of the countries to the east of the old curtain: East Germany, Poland, Ukraine, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Slovenia.

There are plenty we’ve not yet visited, but of those we have, one thing is clear: there is a huge variation in them. ‘Eastern Europe’ doesn’t really exist. Landscapes, languages, alphabets, religions, economic prosperity, you name it, they’re all different. Not that I knew that until we left on a couple of long tours, which would take us through many of them. To me, the ‘east’ was the east, a broken and abused part of the world.

Trabant, Hungary

We travel by motorhome as it gives us the freedom stay in places you wouldn’t normally be able to, and to make daily decisions on which direction to take. Our van is just under 6m long, so fits in a standard parking space, with a little overhang.

That said, it still has everything we need inside, a bed, washing and sanitary facilities, a kitchen, hot and cold water, blown air heating, and a small fridge-freezer. Being well-equipped helped us out more than once in the east since not all countries have the same level of camping facilities we in the UK are used to.

Slovenia & Croatia

Our first experience of driving in ‘Eastern Europe’ was both a disappointment and a delight. Crossing from northern Italy into Slovenia, I was quickly disabused of my notion the east was uniformly grim.

The road was smooth, the fields around us green and well kept, each holding a strange wooden structure we later realised was used to dry grass. Not a depressing tower block to be seen, just the occasional alpine-style polished chalet.

Our first stop was a campsite by the too-pure Lake Bled. The campsite facilities were top-notch; we could easily have been in Austria. Where was the east? Where were the grey crumbling signposts of failed communism? Not in Slovenia, that was for sure. The capital, Ljubljana, also confirmed the ‘east’ wasn’t cheap, at least not this part, as a car park attendant attempted to extract €20 from us for a few hour’s luxury of being stationary.

Entering Croatia, we drove down the Adriatic coastline; alongside waters the inviting blue-green of a cut gem, all Venetian coastal towns and heaving campsites.

The Croatian police have a ferocious reputation for ensuring no sleeping happens outside of campsites, so on campsites of varying qualities we stayed. On one we were whisked around in an electric buggy to choose our pitch, others were just a field of trees offering much-needed shade for our hot tin box.

Reading up on where we were, it quickly became clear Slovenia and Croatia were the tourist cash-cows of the former Yugoslavia, so were kept pristine to draw in much needed hard currency. It would later become clear Yugoslavia adopted a very different style of communism to the countries to the north and east.

A Croatian Sunset over the Adriatic

Bosnia and Herzegovina

While both Slovenia and Croatia are very much on the tourist trail, swinging north from Dubrovnik into Bosnia and Herzegovina saw us fall off the radar almost immediately.

The border crossing in the hills was manned by uniformed guards, swilling bottled lager as the mid-morning heat built. A suited man slapped his leather wallet as he sold us five day’s insurance for an extortionate amount. The sum on the receipt was strangely less than the amount he’d pocketed.

Our first stop in Bosnia and Herzegovina was a town pock-marked with bullets. A rusting sign warned of landmines from the last Balkan war. Our map showed nigh-on no campsites.

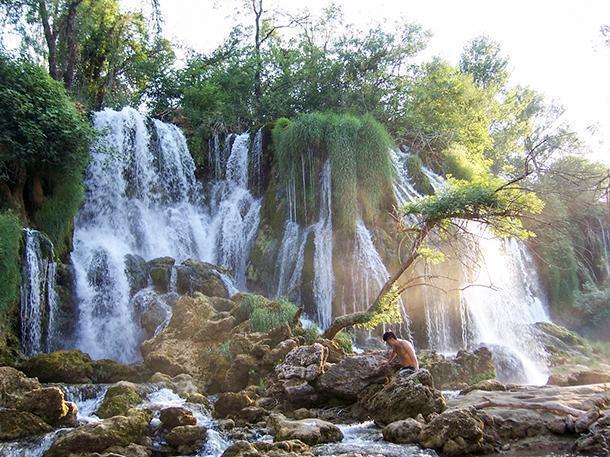

Nervous, and roasting in 40-degree heat, we found unexpected sanctuary in the cool of the sunken waterfalls at Vodoprak Kravice. Walking from the car park above, a Swedish teenager spoke to us in English, words flying out fast, like bullets from a machine gun. “I hate this place; it’s a f**king oven.” He told us, after relaying the fact his family had moved to Sweden when the fighting had started, and he’d learned English from computer games.

Down a ramp we ambled, into a broad bowl, falls cascading on all sides. Locals splashed about in relief while the young and brave leapt dramatically from the heights.

Vodoprak Kravice, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Crossing Bosnia and Herzegovina was a challenge for me, in attempting not to look for evidence of conflict. Just outside Mostar we arrived at one of the city’s few campsites, surprised to find the owner stood in the road waving us in. It seemed the ‘tourist info’ office in the city wasn’t as impartial as it might have been, but the experience proved fascinating.

“I’m a Muslim, I don’t drink,” the young owner told us, as we supped homemade grappa and the ice cold beer he poured for us. Staring past our host at the mortar shells on a ledge behind him, I asked if the man stood by a lathe in the framed photo was his grandfather. “Huh?” he looked around, “No, that’s Tito. He was good for our country”. Oops, my ignorance again laid bare.

Camping Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina

After a couple of fascinating days in Sarajevo, other such evocative experiences of Eastern Europe had to wait.

The road took us north out of Bosnia and Herzegovina across inland Croatia where no tourists go. Here the police pointed us to a communal outdoor swimming pool in the woods, still busy with locals, for somewhere to sleep for free.

From there, into and across Hungary, where we spent a few days relaxing alongside the shallow inland sea that is Lake Balaton, before heading for Budapest via a huge Tesco.

Very much back on the tourist trail now, we crossed the non-existent curtain back into Austria for a while before heading to the Czech Republic, again another well-travelled destination.

Beautifully smooth lager aside, the country offered another rather less enticing drink: at Marienbad, you can sample over 100 natural sulphurous springs. We managed just a few, our faces twisting in humoured distaste with each sip of the hot stinking liquid.

Greece & Bulgaria

The following year we spent longer in the east, crossing from Greece into Bulgaria, through into Romania, Ukraine and Poland before finding safe haven back in Germany. This was the section of travel which really revealed the east of Europe to us.

Before we left Greece, advice rolled in to be careful. Bulgaria and Romania especially. Why we wondered, our nerves on edge as we crossed the manned border into Bulgaria.

The signs went Cyrillic, another challenge to navigation and immediately reinforcing the change. Greece never adopted a communist government, so crossing this border had dropped us back into the ‘east’. Eating a meal out on our first night our waiter told us how rich the Greeks are compared to them “they can afford to fill their cars with diesel”.

Horse and Cart, Bulgaria

Unsurfaced Side Road, Bulgaria

After a spell in the mountains above Bansko, we travelled north to a great bastion of Bulgarian culture: the Rila Monastery, where we spent the night in the car park by the main door.

Here the Bulgarians have kept their traditions alive as successive invaders attempted to clear them away. Unsurprisingly, the monastery is well-visited. We made the most of the fact we were there after the last coach left in the evening before the huge wooden doors closed for the night.

Rila Monastery, Bulgaria

Scrapyard, Bulgaria

Near the monastery lie the seven Rila lakes. If you arrive early enough (we didn’t), and wear suitable footwear (we didn’t), you can take a cable car up to the lowest of them and make a fairly easy hike up the hillside where you can see all seven at once.

Our attempt was woeful, only three lakes visible from our highest ascent, but nevertheless the view was as uplifting as the air was clear and cool. That night we slept well at the foot of the chairlift, despite the excitement at the possibility of spotting a bear wandering the forest around us.

Three of the Seven Rila Lakes, Bulgaria

In Plovdiv, a city rapidly evolving into a tourist destination, we stood awe-struck at the sheer presence of a huge, stone Russian soldier, holding a machine gun, forever looking out from one of the city’s hills. The Red Army ‘liberated’ Bulgaria from the Germans, even though the country allied itself with Germany in WW2, a complex mystery I’ve never worked out.

Alyosha Monument, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Our method of travel often takes us to smaller towns, simply as we have some information that there is somewhere safe for us to park. In Bulgaria, we found ourselves parked in a square in the centre of one such town called Tryavna, renowned for wood carving.

Here we enjoyed a beautifully cooked meal, for a beautifully low price and, at the end, found we’d been sitting next to a British couple. They’d left the UK to buy and renovate property in Bulgaria, and regaled us with astounding stories of buying entire houses and grounds for a few thousand euros.

When we finally returned to the UK to look for work, their story rattled around my head as I wondered whether we could escape the corporate life for Bulgaria. I couldn’t shake the feeling the country was culturally somewhat desolate, though, a feeling I can’t offer much evidence to support.

Romania

Despite an increase in the number of horse and carts sharing the roads with us as we moved into Romania, the country felt affluent compared with Bulgaria. This was helped by the brand new tarmac being laid when we passed through, like a welcoming black carpet.

The country makes much of the mythical association with Dracula and, in parts, the tackiness was just too much. The two places in Romania that abide in my memory were Dracula free: the top of the Transfăgărășan Pass, and Sibiu.

The pass, more prosaically known as the Drumul Naţional 7C, was made famous by a Top Gear episode, where the presenters raced up the unlikely road over the Făgăraș Mountains, declaring it to be ‘the best road… in the world’.

Our experience was of wonderful scenery, and a chance encounter with young snowboarders making the most of the high snow in July to leap from a kicker they’d built. I grabbed a few photos for them and, in return, they shared their dad’s 50% proof plum moonshine with us. We slept the night on the pass among the caravans used by the many stall owners, before making the incredible, but simple descent the following morning.

Transfăgărășan Pass, Romania

Sibiu was placed on our radar by a long distance motorbiker at the top of the pass, who told us Red Bull’s Romaniacs hard Enduro Challenge ended there in a couple of days. Somehow we found the field where the event would take place, no signs were evident and we guessed our way there to a large extent. The event was astounding to watch, as bikers valiantly tried to hurl themselves up a huge, steep hill at the end of days of tough riding. The announcer declared those who decided it was one madness too far, and took one of the escape paths to the edge, had ‘taken the chicken line’!

The owner of the nearest house, which sat alone at the end of a dirt road leading to the finish area, invited us in for breakfast the next day, having already ensured we’d spent a memorable evening in Sibiu the night before. Romanians, from our experience, are wonderful people, who can’t understand why us English folks say ‘thank you’ quite so much!

Red Bull Romaniacs, Sibiu, Romania

Ukraine

The decision to leave Romania via Ukraine led to perhaps our most potent experience of ‘Eastern Europe’. The border crossing left us in no doubt we’d left behind the EU, as we stood in line wondering what was in the thick dossier of paperwork the other people entering the country were clutching.

An official in Soviet-style uniform impatiently demanded our papers, stared at them for an inordinate length of time before violently stamping at them and practically flinging them back at us. “Is that it?” we wondered, could we go? Nope, shuffle forwards to the next area, and so on.

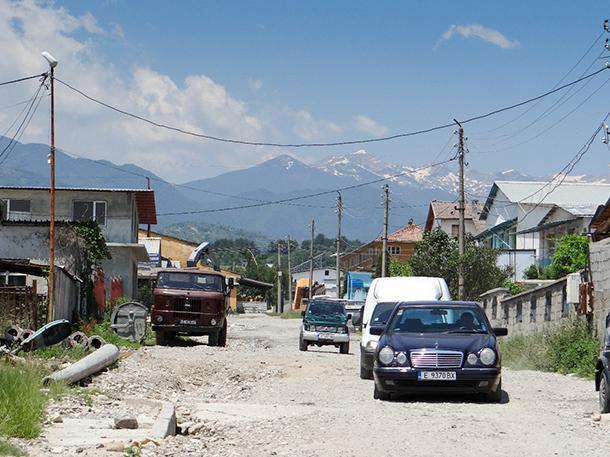

Inside the country, the road surface physically attacked us with holes so enormous the traffic turned into a snake, as everyone in both directions competed for the same tortured route of relatively flat stuff. A Lada had fallen at one point, a wheel snapped off.

The feeling we’d bitten far more than we could chew arose in our throats, and we wondered about turning around. It was culture shock, we’d experienced before, but that was crossing into Africa. Just moving between two Eastern European countries, we felt the same shuddering awareness that we weren’t in Kansas anymore, Toto.

With zero campsites for a hundred miles and no known places to stay, we asked at a city hotel if we could stay in the car park. Probably not understanding we had a motorhome with a bed (the border guards enjoyed a look around inside the van, raising their eyes at the luxurious fittings), they said no, and we rumbled along the road.

Finally, we spotted a car park next to a bar and pulled in. After the tricky job of again explaining we didn’t need a room, during which a Spanish speaker was rounded up to communicate with ‘the foreigners’ (we don’t speak Spanish), they finally understood.

At this point the locals couldn’t have been more helpful, moving cars to get us the best parking space alongside a wall. Nipping in to have a beer to repay them, our jaws dropped at the marble and glass interior. Outside the roads resembled ploughed fields, but in here the light glinted and shone.

It wasn’t a bar, it turned out, but an events centre. Sitting in the motorhome later, we saw car after car bounce slowly down the road and finely-clad folks climb out and walk across the mud to the entrance.

Poor Road Surface, Ukraine

Tyre Highlighting Missing Road Cover, Ukraine

While it seemed like no one had taken their motorhome across Ukraine, we knew they must have. That night, we did our homework and came up trumps: a TripAdvisor review noted a guest house called ‘On the Corner’ on our route back towards Poland at Kolomyya had once allowed a motorhome to stay on the drive. Sending a hopeful email, a reply was there by morning: “Come on over”.

Sign at Entrance to Kolomyya, Ukraine

Communist Statue, Kolomyya, Ukraine

We stayed a couple of nights on Vitaliy’s drive, a wonderful experience. He took us to the nearby folklore museum, explaining with obvious passion how his ancestors had lived. “See those bells? The wife would wear those and walk behind the man, so if she was attacked by a bear or a wolf, he would know about it”. We checked, he wasn’t joking.

Over delicious hand-crafted meals cooked by his mother, surrounded by young US Peace Corps volunteers taking a break from working in Crimea, he shared stories of Russian occupation and Ukrainian corruption. We lapped it up, especially when he let on he was a trained lawyer but refused to practise as “whoever has the fattest brown envelope wins”. Wary of stories of underpaid Ukrainian police pocketing fines from foreign drivers, we gratefully accepted his business card and the offer to “tell them to call your lawyer”.

Vitaliy, Ex-Owner of On the Corner Guesthouse, Kolomyya, Ukraine

Russia annexed Crimea in the months after we left amidst a civil war, forcing the Peace Corps volunteers to go home and perhaps acting as the nudge Vitaliy needed to finally leave his beloved hometown. He’s now living in Canada with his wife and son and is running a hotel.

Eastern Europe, to me, has many facets. The countries within this vast area are well worth exploring, especially away from the capital cities, where ‘westernisation’ is slower to take place. Our feeling was the towns and cities were no more or less dangerous to travel than those to the west of the curtain but in many cases far more fascinating. Go see ‘em, have fun.

Julie and Jason’s blog www.ourtour.co.uk lists the GPS coordinates of all the places they stop on their travels.

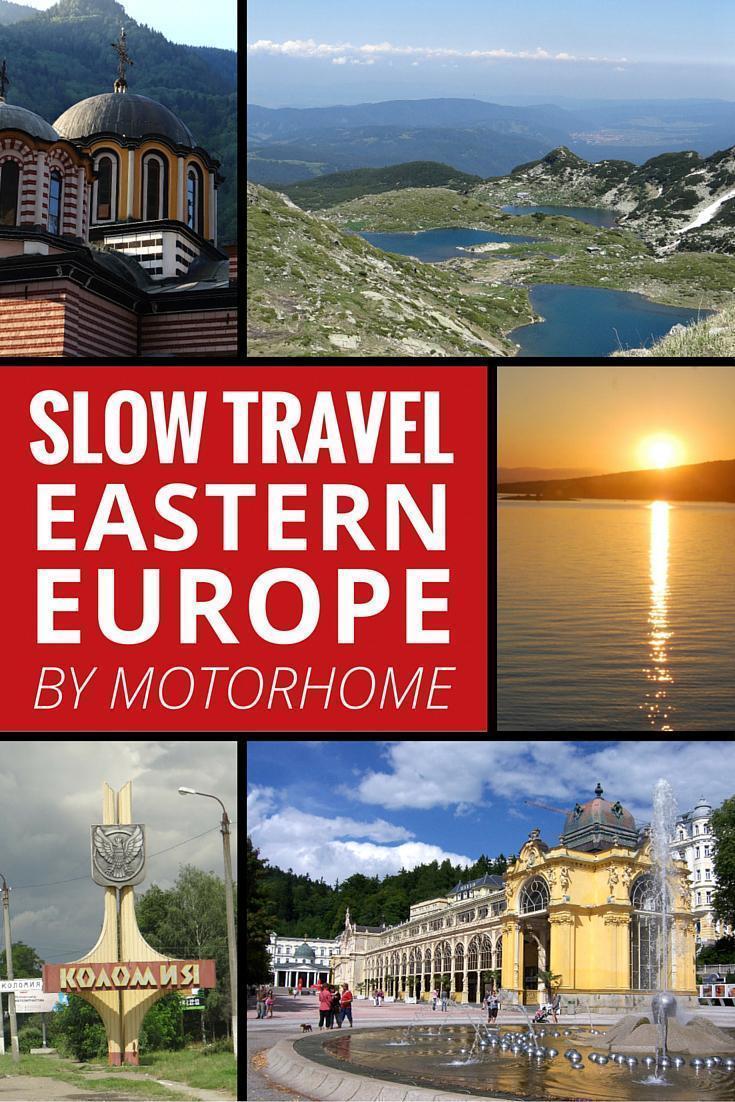

Like this article? Save it to Pinterest!

- Slow Travelling Eastern Europe by Motorhome - April 19, 2016