France has crepes, the Netherlands has poffertjes, China has cong you bing, Russia has blini. All around the world, humans eat some form of flattened fried dough. Here in Canada and the US, we all know about pancakes; made with regular or buttermilk, topped with fresh fruit or jam, or delicious Canadian maple syrup. But there’s another type of pancake found in New Brunswick’s Madawaska County, which has also trickled across the border into parts of Quebec and Maine, most people haven’t heard of.

Of course, we had to eat it.

What the heck is a Ploye?

“If you’re going to Edmundston, you have to eat a ploye.”

Besides visiting the New Brunswick Botanical Garden, this was my mother’s top tip for the Madawaska region. A passionate baker, my mom shares Andrew’s sweet tooth and love of all breakfast foods. Personally, a savoury gal at heart, I can take pancakes or leave them, although I did fall for the savoury Breton crepes. As they’re buckwheat-based, as well, maybe ployes would be right up my alley…

Normally, when we visit a new region, we endeavour to eat its most famous food as soon as possible. However, it wasn’t until our final day in Edmundston we got to eat a freshly made ploye, hot from the griddle.

First, we had to learn what makes a ploye a ploye – the short answer is buckwheat. If we were going to learn about ployes, we had to go to the source.

We began our ploye journey at the village of Clair, 30-minutes from Edmundston on the St. John River. Incidentally, it’s a beautiful drive with only the mighty river separating Canada from the USA. I had grown up crossing this river at its mouth, almost every day, but had never seen it this far north. It’s a genuinely impressive body of water. But we were here for land-based pursuits.

We arrived at Les Industries Corriveau, a family farm, where we met Jamie Corriveau, whose family has been growing buckwheat, (or sarrasin, in French) since 1893. Jamie took the reins of the family business in 2012, from his father, who still works on the farm.

Jamie led us into a small barn, where his father, Guille Corriveau, was hard at work milling buckwheat in much the same way as it has been done for generations.

Milling buckwheat the old-fashioned way, at Corriveau Industries

Buckwheat Flour Production

We stepped into a cloud of fine, white, buckwheat dust, and Jamie shouted explanations over the racket of the mill. The entire operation is run by an ancient tractor, parked (permanently) just outside the barn.

One ancient tractor runs the whole buckwheat mill.

Covered in buckwheat flour, the old mill chugs away noisily.

Jamie showed us the raw buckwheat in its dark brown husks. We watched it pour down into a sifter before the husk is removed. The result is a course, golden flour. But it’s not ready for ployes just yet. The finished product is ground down to a fine powder, as soft as silk, with just a hint of the yellow colouration remaining.

Raw buckwheat needs the dark husks removed

The buckwheat husks

Buckwheat after the first grind

Soft as silk, the fully milled buckwheat flour

I looked at a stack of sacks in the corner and asked if they contained buckwheat flour. Jamie shook his head and told me they were buckwheat husks which would be sent to a company that makes pet beds. Buckwheat is a versatile product.

Bags of buckwheat husks destined to become pet beds

Now that we had seen the end result, we needed to see where it all began. We followed Jamie to one of the many fields in the area (175 acres worth) growing his buckwheat. We walked into the short, bright green leaves and Jamie told us a bit about this unique plant.

The Corriveau’s have fields of buckwheat scattered across the region

The Buckwheat plant isn’t wheat at all. It’s related to rhubarb.

Watch how Buckwheat is converted from field to flour in our short video.

What is Buckwheat?

Like most folks, I assumed buckwheat was, in fact, a grain, like wheat. However, buckwheat isn’t a grass at all; it’s actually in the same family as rhubarb. As it’s not a wheat product, buckwheat is naturally gluten-free – a characteristic Jamie recognised has a unique selling proposition these days. With the rise of gluten allergies and intolerance, buckwheat is garnering more demand, and the market reaches beyond baked goods. Jamie has been working with a craft beer brewery in New Brunswick to produce a gluten-free beer made from his buckwheat. The project has been in the works for some time, and Jamie hopes the product will come to fruition soon.

gloriously gluten-free buckwheat flour

Ground buckwheat ready to be bagged and sold as a gluten-free alternative

Unfortunately, traditionally made ployes are not gluten-free, as the buckwheat flour is mixed with regular wheat flour. Corriveau Industries produces a ploye mix containing all the dry ingredients necessary to make ployes at home: buckwheat flour, white flour, baking powder, and salt.

Buckwheat (and gluten-free beer) isn’t the only trick up Jamie Corriveau’s sleeve. He also produces the ploye’s best friend – maple syrup (because honestly, what’s a pancake without maple syrup?)

Making Maple Syrup

We followed Jamie’s truck out to Lac Baker (Baker Lake), about 15kms from his farm, where he and his wife, Cindy, run Erablière Unique (Unique Maple). As it was summer, the large warehouse containing the maple syrup-making equipment was silent. Come early spring, during the brief period the sap runs, it will become a hive of activity.

Andrew takes a look at the huge vats that will hold the maple sap

‘The Inferno’ heats the sap to boil it down, creating maple syrup

Erablière Unique produces maple syrup and sugar as well as treats like maple taffy, maple butter, and maple caramel. In season, you can visit and tour the operation by reservation, and there are family weekends and events.

We braved the voracious mosquitoes for a quick visit to the maple trees. Although it was quiet, Jamie explained the intensive amount of work that must be completed, by hand, in a short time-frame. It’s easy to see why real maple syrup comes at a much higher price than that well-known Aunt’s pancake syrup – and why it tastes so much better too.

The maple forest is quiet now but will be a hive of activity in the early spring

Eating Ployes – Finally

But after all this talk of ployes and maple syrup, we still had yet to taste this delicacy. The following day we got our chance – twice.

Our first ploye experience was a non-traditional one. We picked up a picnic lunch from Maurifils Farms (a fantastic farm shop we’ll tell you all about in a future article) and grabbed a picnic table on the Madawaska River, overlooking Edmundston’s iconic pedestrian bridge.

Opening our lunch boxes we discovered our sandwiches were a truly Brayon affair, made with ployes instead of bread. They were delicious, but we still had to taste the traditional ploye, hot from the pan, with butter and maple syrup.

Ployes make a delightful alternative to bread in our sandwiches

How to Make a Ploye

The very last thing we did in Edmundston was a foodie tour of the downtown (full details to come), and the final stop on the tour was the tourism office. There, our cheerful guide donned his apron, heated up a griddle, and set to work.

Bubbles are essential when mixing the ploye batter

“You have to mix it just right,” he told us as he beat the batter. “The bubbles are essential.”

The batter is thin. “A good consistency should look like wet paint.”

The ploye batter should be the consistency of wet paint

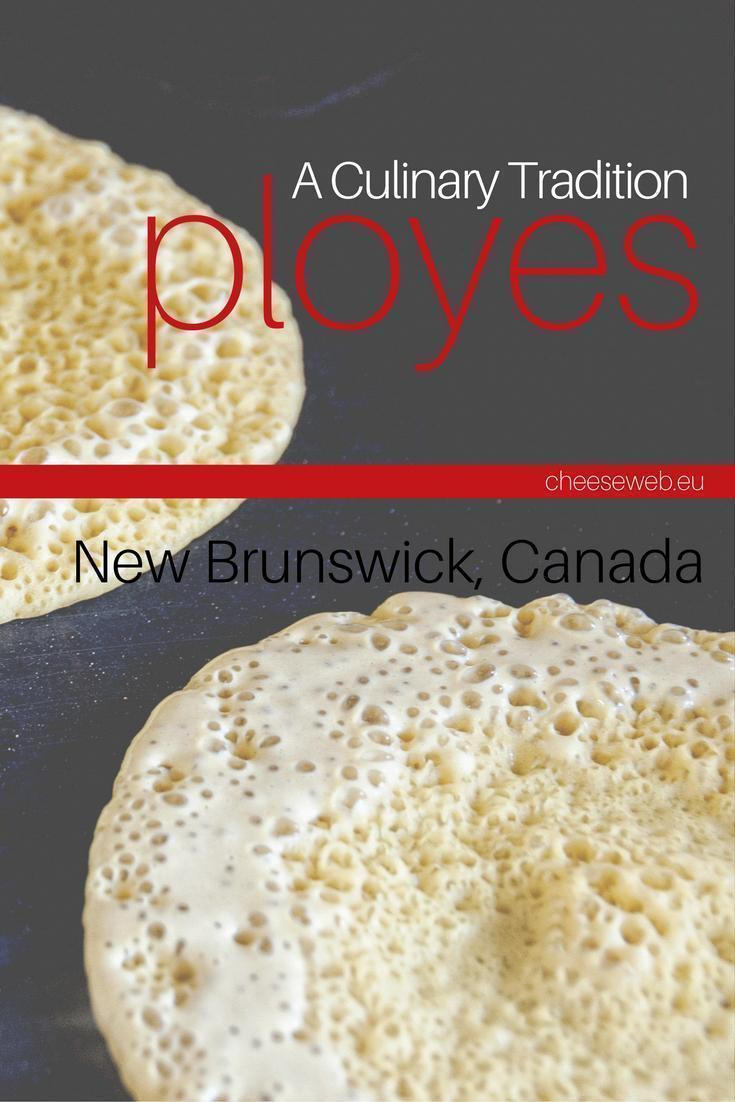

Unlike regular pancakes, you don’t flip a ploye. It cooks on one side, allowing the bubbles to form and burst, leaving pillowy air pockets.

Never flip your ploye or it will ruin the bubbles

It didn’t take long for the batter to turn golden. Our chef deftly scooped the hot ploye into a napkin and sprinkled it with maple sugar.

The finished ploye with butter and maple sugar – perfection.

Hot. Buttery. Sweet.

Definitely worth the wait.

We’d like to extend our thanks to Jamie Corriveau for taking the time to teach us about buckwheat and maple syrup production and Tourisme Edmundston for hosting us in the area and allowing us to share this hidden gem with you. As always, all opinions are ours alone.

Like this article? Save it to Pinterest!

- The Ultimate List of Castle Hotels in Belgium - June 10, 2019

- The Ultimate Guide to the Best Things to Do in Normandy, France - February 5, 2019

- The Ultimate Guide to the Best Restaurants in Brussels, Belgium - January 11, 2019