Sending expat kids to school in a new language can be terrifying for parents

Today we are thrilled to share a guest post from Michelle, an American expat living with her family in Umbria, Italy. She writes about overcoming her fears, finding her voice in a new language, sending her kids off to an Italian school and learning to take things one step at a time – Challenges expats everywhere can relate to.

My whole life, I’ve strived to be perfect. Not to garner admiration or accolades, but rather to avoid falling short. As a coping strategy, I admit, it is dreadful. I walk around anxious that I’m not meeting some standard, and so I end up going above the call of duty just to make sure I’m hitting the mark. Well, being an American expat in Italy is going to knock that annoying personality trait right out of me—particularly being an expat with three children in public school, when none of us speak the language, and have no idea what’s happening half the time. There is no way I can be perfect, so the striving to be so becomes more of a phantom-limb phenomenon than a relevant part of my everyday existence.

My first inkling of this came when I asked my landlady if the fish market sold legs. Legs, you see are gambi, not that different from shrimp, which are gamberi. She gave me an odd look and ignored the question; only later did I realize my error. I’ve made that mistake only once, but I routinely confuse pesca (peach) and pesche (fish). In my defense, almost everyone in my family has confused the two words—to much public snickering—but I did it first, and did it last, as I just told my Italian teacher that I enjoyed some amazing fish beer when I was in Brussels. In my former life, I was a psychologist with a thriving practice. I was looked to as the person with the answers, with the chutzpah to tell other people how to run their lives. Now, I can’t be trusted to bring home a bag of peaches from the ortofrutta without embarrassing myself.

This sort of public imperfection would be hard enough, but combine it with my general fear of trying to speak another language, and it was initially overwhelming. I backpacked through Europe when I was in college, and I don’t remember being this consistently nervous about making a mistake. I would do my best, and my voice would at least approach normal volume. But as an adult, I’ve developed a misbegotten notion that the quieter my voice, the more respectful I’d appear. I suppose this could have worked if I’d been an expat in more reticent societies, but in Italy it goes nowhere. It’s only been when I’ve stopped pushing my husband forward to speak—when I’ve found my own voice—that my anxiety around speaking has lightened to wisps of fog that sometimes thicken and choke me, but mostly just float about as a reminder of my latent insecurities.

Then there’s school. Sending my children off to public school that first day was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do as a parent. There were moments before that day when I actually started calculating how much it would cost to purchase last-minute tickets home, because there was no way I could subject my children to this kind of bone-chilling unknown. My youngest is five, and I was pretty sure there would be at least one point in the day when he’d wonder if he would ever be allowed to go home. The only way I was able to wave the kids off with cheer and support (rather than falling completely apart at the seams) was by realizing that it would be hard, but they would be okay. It sounds so simple, but really, it was and incredibly comforting thought. When I said goodbye to them, my legs were still weak as if my joints had been replaced with aspic, and my face clearly noted a significant amount of alarm because my baby’s teacher felt the need to run up and kiss me and order me to relax, but (and this is a major but) I was able to refrain from both camping out in front of the school, and hooking spy cams on to my children. For the record, they all had a stellar first day.

Living abroad can be tougher on expat parents than on their children

Before school started, everyone—from Letizia who makes me my cappuccino in the bar every morning, to Arturo who teaches me Italian in a room of his home that looks like Fellini movie set-piece—kept telling me, “piano, piano, piano, e tutto bene” (“slow, slow, slow, and everything is okay”). This seemed, at first, pretty condescending to me; along the lines of telling an arachnophobe to just calm down in the presence of a jumping wolf spider. But now I’ve realized this isn’t a platitude, it’s a way of life. I hear it all the time, and not just in conjunction with placating high-strung Americans. I’ve realized now what it means: “One step at a time, and everything will be well.” Beautiful. Exactly what my tender soul needs to hear again and again, to keep myself from jumping to the conclusion that people will think I’m a bad person because I didn’t sign my children’s forms on the day that they were distributed. Piano, piano, piano. Now Letizia puts a dash of cocoa powder on my cappuccino. It feels like a benediction.

Yesterday, there was a strike at school. I’d forgotten, even though I’d had to sign the circular that said there might be a strike. It was the third such circular in three weeks of school, none of which culminated in a strike, so I guess I treated it like a card in the game of Life. So I didn’t accompany my middle school son to school. And he didn’t have our phone number to be able to call us so we could fetch him back. Finally, the secretary realized that she would have his number on file, he called us, and we picked him up. He had a nice, cozy day until he found out through Facebook that the students were supposed to return to school at 10:00. This makes zero sense to me, but then again, neither does the post office, and somehow we just go along with it. So, perhaps I’m the negligent parent who didn’t get her son back to school. That’s okay. We’re just figuring it out. It’s a constant refrain in our house.

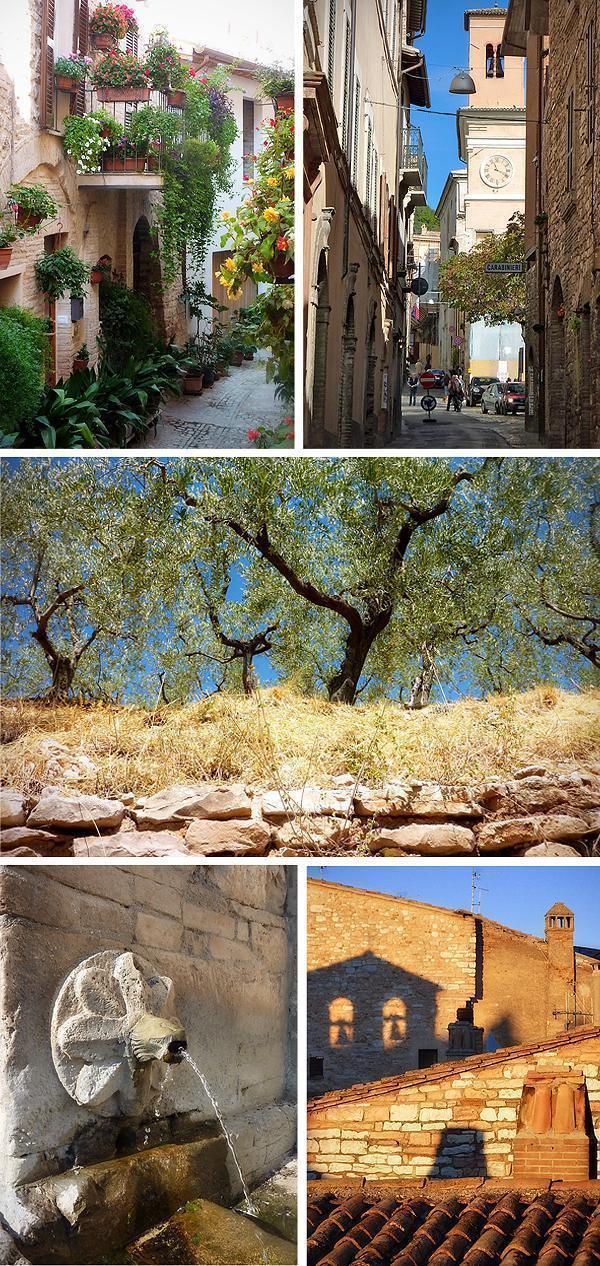

Scenes from Umbria (All of the beautiful photos in this post have been supplied by Michelle).

No one in my medieval hilltop village pretends to have all the answers. Nor do the Italian tourists who flock here after a day in Assisi, and that is so comforting. They stop and ask me for directions, or what’s at the top of the wall, or how to find a good restaurant with no qualms about not appearing in full command of all relevant knowledge. Maybe the urge to always have information is uniquely American. Before we left for Italy, my eldest child had a hard time asking where the office was when he took a summer high school course. Here, he had to ask three people just to find his classroom on the first day of school. I have found that by asking my Italian teacher why no local olives are sold in the market, I will not only get a lesson in the olive culture of our region, but also an offer of a tour of a nearby frantoio, where oil is pressed. I have learned that only by asking the barrista what that intriguing-looking melon-colored cocktail is, can I unlock the secret that is an Aperol spritz. I have told the police officer processing my residency paperwork that I have no idea what he is saying, and somehow I am able to get my permesso paperwork processed anyway. It’s humbling, in the most wondrous way.

We’re just figuring it out. We’re none of us perfect. And how nice that it’s so. Imperfect means we have room to learn, to grow, to feel our vulnerability. And that’s actually kind of beautiful.

Even if the fishmonger still chuckles every time he sees me.

- Back on Home Soil – Coping with Reverse Culture Shock - November 26, 2013

- Peaches and Fish – Language and Uncertainty in Expat Life - October 19, 2012